1. Morning Fog and the Ferry to Alcatraz

A veil of fog settled over the San Francisco Bay as I walked toward Pier 33. It had the kind of ghostly charm that belonged in a 1940s film noir, and it fit the destination all too well. Alcatraz Island loomed in the distance, visible only in silhouette. Seagulls hovered like wardens in the air, and the wind carried a biting chill that seemed to whisper old stories.

The ferry to Alcatraz felt less like a ride and more like a passage—over water, through time. The ride took only 15 minutes, but the transformation was immediate. The city skyline faded behind me, and the rock of Alcatraz drew closer with every churning wave. No matter how many pictures I’d seen of it, the real thing was a cold and proud fortress, framed by barbed wire and layers of faded paint. The scent of salt and rust filled the air.

Stepping onto the island, the first sound was the squawk of gulls and the crash of waves. Then, silence. A strange, oppressive silence. I wasn’t walking into a tourist site; I was walking into a memory.

2. The Cellhouse: Echoes Behind Iron Bars

The walk up the hill to the cellhouse is steep, as if to separate ordinary freedom from the weight of confinement. At the top, the cellhouse doors open with an industrial clang, and the first impression is purely sensory: concrete, metal, mildew, dust, silence.

The cells are smaller than they appear in photographs. Narrow, narrow enough to make a grown person feel like the walls were too close, even when they weren’t moving. Everything here is measured—width, height, duration, routine.

Each cell has its own story. Some are filled with small artifacts: a chess set, a radio, a handwritten book of poetry. It’s hard to ignore the defiance of creativity within a system designed to suppress it. The most haunting section, the solitary confinement cells—known as “the Hole”—are pitch dark and acoustically dead. I stepped inside one, let the door shut for a moment. In those seconds, time ceased to exist.

The audio guide was narrated by former guards and inmates. Their voices filled the corridors with recollections of escape attempts, prison riots, and the boredom that eroded men’s minds like slow acid. It was the kind of boredom that sharpened edges—of violence, of thought, of regret.

Out of all the inmates, Robert Stroud—the “Birdman of Alcatraz”—left a mark. Not because of the Hollywood dramatization, but because he managed to study and write on ornithology while imprisoned. It was another reminder that even on the Rock, the mind could fly.

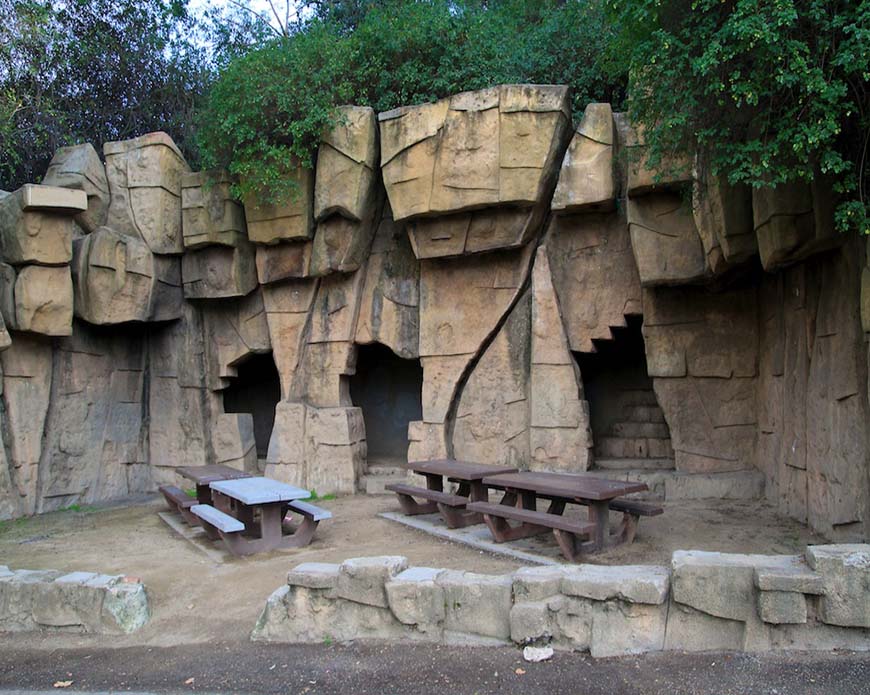

3. A Landscape of Contrast: Gardens of Alcatraz

Outside the cellhouse, I didn’t expect to find color. But Alcatraz has its own quiet defiance. Inmates once cultivated gardens here—roses, succulents, geraniums—planted in soil carried up by hand. Today, these plants bloom with quiet persistence. Amid barbed wire and guard towers, bees hum and petals open.

A volunteer gardener shared stories of how the gardens provided a form of rehabilitation, not just for inmates but for the island itself. Walking those paths felt like stepping into a different kind of resilience—one that grew instead of punished.

4. Crossing the City: Streetcars, Sourdough, and Slopes

Back on the mainland, the city opened up like a maze of cinematic backdrops. The clatter of a passing streetcar sounded like applause on rails. The California Street cable car line carried me uphill, cutting a dramatic path through Nob Hill. Outside the window, the city’s patchwork of Victorian houses, muraled alleys, and leafy parks created a kaleidoscope of eras.

At lunchtime, I made my way to the Ferry Building. Beneath its high arches and century-old clocktower, vendors sold artisanal cheeses, hand-cut pasta, and loaves of San Francisco’s legendary sourdough. I tore a piece from a warm round and tasted a crust so tangy and chewy, it felt ancient. Bread that had risen during the Gold Rush still rose today, thanks to a wild yeast unique to the Bay.

A short walk brought me to Coit Tower. Painted during the 1930s as part of the New Deal’s Public Works of Art Project, its interior murals captured Depression-era labor, protests, and daily life in bold color and radical style. These paintings weren’t just art—they were declarations.

5. North Beach and the Ghosts of the Beat Generation

North Beach wears its past like a coat thrown over its shoulder—half style, half necessity. On Columbus Avenue, Vesuvio Café sits across from City Lights Booksellers. I stepped inside the café, ordered a cappuccino, and took a seat where Kerouac might have scribbled his last sentence.

City Lights is a cathedral of paper. Stacks of dog-eared copies of Howl rest beside anarchist zines, rare poetry volumes, and philosophical tomes. A sign above the stairs reads: “Open Door, Open Mind.” That ethos still vibrates in every shelf. I spent an hour thumbing through worn pages, overhearing snippets of conversations that drifted like the jazz soundtrack playing low in the background.

In Washington Square Park, old men played chess and argued politics under trees older than the neighborhoods themselves. Saints Peter and Paul Church rose behind them like a guardian, its white spires gleaming in the early afternoon sun.

6. Chinatown: Layers Beneath Lanterns

Grant Avenue welcomed me into Chinatown through a dragon-topped gate. The smells of incense, roasted duck, and star anise formed a moving tapestry. The pace here was brisk, the language a mix of Mandarin, Cantonese, English, and memory.

Beyond the souvenir shops, the Chinese Historical Society Museum revealed a deeper narrative: exclusion acts, resilience through railroad labor, and a thriving culture built in defiance of erasure. The upstairs galleries held personal artifacts: wedding dresses, herbalist tools, immigration documents. Downstairs, a video looped testimony from descendants who spoke of rice cooked with lard in the early tenements, of games played with rocks when toys were luxury.

In the alleyways, murals told stories unspoken in official records. I stood before one that depicted a grandmother weaving, surrounded by ghosts of ancestors. History, here, wasn’t just in the past. It breathed.

7. The Presidio: Where History Marches with the Wind

The Presidio once guarded the western edge of an empire. Now, it serves as both memory and monument. The Spanish established it in 1776. Later, the U.S. Army moved in, and for over 200 years, soldiers marched, drilled, and saluted across this land.

Today, it offers long walks under eucalyptus trees, where old barracks have become museums, art studios, and film centers. In the Presidio Officers’ Club, I found an exhibit on the Buffalo Soldiers—African American cavalry units whose history remains largely untold in textbooks. Photographs of solemn faces, uniforms pressed and proud, stood against sepia backdrops of duty and hardship.

I sat near the Main Parade Ground as a foghorn groaned in the distance. The air was thick with nostalgia and salt. Even the architecture held its breath here—red-tiled roofs, whitewashed walls, symmetry that spoke of order in an ever-rebellious city.

8. The Palace of Fine Arts: A Temple to Beauty

Dusk found me at the Palace of Fine Arts. Golden light dripped from the columns like honey. The rotunda stood like a mirage, a Roman dream washed ashore in the New World. Swans moved across the lagoon, indifferent to the tourists photographing every curve.

Designed for the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition, the Palace was meant to celebrate rebirth—San Francisco’s recovery from the 1906 earthquake. The architecture, inspired by classical forms, somehow avoided feeling like imitation. It was pure stagecraft, and it worked.

Under the dome, I stood quietly, listening to the acoustics catch every whisper. The Corinthian columns were stained with time and light, and even the cracks felt intentional. I could almost see the crowds of a century ago, dressed in finery, gasping at electric lights, modern paintings, and orchestras.

Today, it hosts weddings, photoshoots, and late-night musings. But its bones still carry the echo of ambition—of a city determined not just to rebuild, but to astonish.

9. Nightfall in the Mission: Murals, Mezcal, and Memory

Evening arrived with the soft buzz of neon signs and the rhythm of taquería music in the Mission District. The sidewalks pulsed with stories—graffiti layered over murals, Spanish woven into every conversation, street food sizzling on corner grills.

At Balmy Alley, I walked past decades of mural work—each wall a chapter, each image a protest, a prayer, a plea. One showed mothers holding photographs of the disappeared. Another depicted a farmworker beneath a sun of flames and tears. Each artist had stitched themselves into the city.

At a nearby mezcal bar, I sat on a worn stool, sipping a smoky pour served with orange slices and sal de gusano. The bartender talked about local politics and the rising cost of everything. Around us, the air filled with cumbia and laughter.

Later, I walked back toward Dolores Park, where couples lounged under blankets, and the city’s lights shimmered through the trees like ancient constellations trying to be modern.

10. A City Carved in Contradiction

By night, San Francisco is a different shape. It curls inward, quieter, but never still. The city is a paradox: old and new, gold and shadow, painted lady and steel spine. Its history is not cleanly archived. It erupts on sidewalks, in alleys, across stained-glass windows, and through courthouse steps.

The past here is not past. It is performed—through protest marches echoing old civil rights chants, through restaurant menus resurrecting dishes long lost, through libraries and chapels and corner bars filled with the voices of ancestors.

From the stern cells of Alcatraz to the soft arches of the Palace of Fine Arts, from Chinatown’s red lanterns to the brushstrokes of Balmy Alley, San Francisco offered not a tour, but a reckoning. The city didn’t just show itself—it demanded to be known.

And I walked. Past, present, and perhaps even future, all unfolding beneath my shoes.